An outbreak reveals a medical technology blind spot: Tuberculosis testing

Here’s some health news you don’t hear every day: Last month, there was a tuberculosis (TB) outbreak in the U.S.

Don’t worry, unless you’ve recently had surgery and received a bone graft, you’re likely not at risk. But since tuberculosis is a relatively rare disease in the U.S., the news was enough to turn some heads.

The company whose bone grafts were tied to the outbreak is Aziyo Biologics. And unfortunately, this is Aziyo’s second such outbreak. Plus, while this kind of outbreak is uncommon, it's especially deadly for patients whose immune systems are weakened by the immunosuppressive drugs they’re taking for the procedure.

But before you breathe (another) sigh of relief about this outbreak being the fault of a single bad actor, we have some more bad news. The big takeaway from this investigation isn’t that Aziyo was the problem. The U.S.—and many other countries—simply do not have the infrastructure to catch potential sources of TB infections like this. So, unless something changes, another outbreak like this is only a matter of time.

That “something” is TB testing. Specifically, TB testing of devices and biomaterials. In short: Effective TB tests for these contexts mostly don’t exist. But that’s not because they’re impossible. Let us explain.

The TB test status quo

If you’ve ever worked in a healthcare setting, you’re probably familiar with some form of TB testing.

You may have undergone the TB skin test—aka the Mantoux test—where a bubble of fluid injected under your skin helps a clinician determine whether you’ve been exposed to the bacterium that causes TB.

That’s not the kind of TB testing we’re talking about here.

When it comes to donated biomaterial—such as that which is used to create devices like bone grafts—you might assume that it would be thoroughly vetted before being used in a surgical procedure.

But there’s a problem: There is no commercially available TB test for bone tissue. And in the U.S., there’s no regulatory requirement from the FDA or the American Association of Tissue Banks to test donor materials for TB.

The gold standard is a bacteria culture test, but it takes up to 8 weeks for a result and is quite labor-intensive and expensive. On the other hand, the faster nucleic acid tests are prone to false negatives. The FDA has approved only three of these tests—all for “sputum” (aka phlegm), which is more challenging to collect than blood or urine.

Clearly, there’s room for innovation here. But companies developing better tests may not want to undergo the headache of regulatory approval, especially for small use cases like donor bone tissue testing where the existing tests don’t work.

How do we close the TB investment gap?

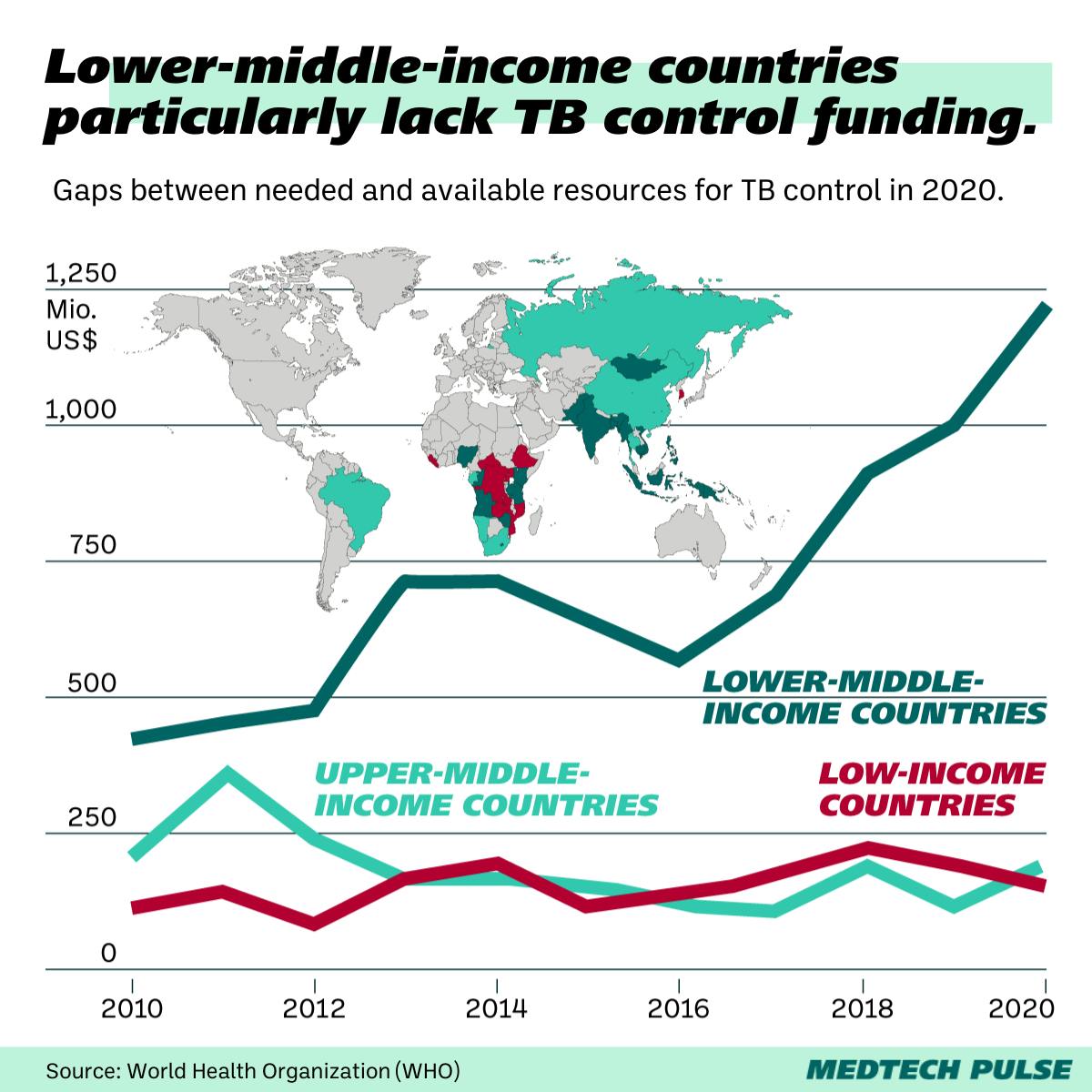

Given the severity of a threat like TB, we need global investment in research and testing (and treatment) for the disease.

You’ll remember we mentioned how rare the disease is in the U.S. But TB has a much bigger public health impact in the Global South, especially in Southeast Asia and Africa. Currently, there’s not enough research investment to meet this need.

Similarly to the limited incentive companies and researchers have to develop a challenging TB test for donor bone tissue, there’s a lack of political will at play here.

Claudia Denkinger, head of the infectious disease division at University Hospital Heidelberg described this trend: “[TB is] a disease of the poor and vulnerable globally. There has been more investment recently through the Gates Foundation and other global funds, but it’s still vastly insufficient.”