This stroke survivor got her voice back after 18 years

For patients with locked-in syndrome (LIS), communication can be a painstaking and depersonalized task. The current technology allows these patients to careful type letter by letter with the use of eye movements.

That is, until now.

A brain-computer interface (BCI) and an AI-enabled digital avatar have helped a woman “speak” for the first time since suffering a stroke at age 30. It has been 18 years.

The patient, Ann, is now helping scientists at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) hone the technology to help others like her communicate more and more naturally. This is the first time that speech or facial expressions have been translated from brain signals.

Join us as we explore Ann’s journey and check in on the latest developments in BCIs and digital avatars in medicine.

How a BCI can help all the other Anns out there

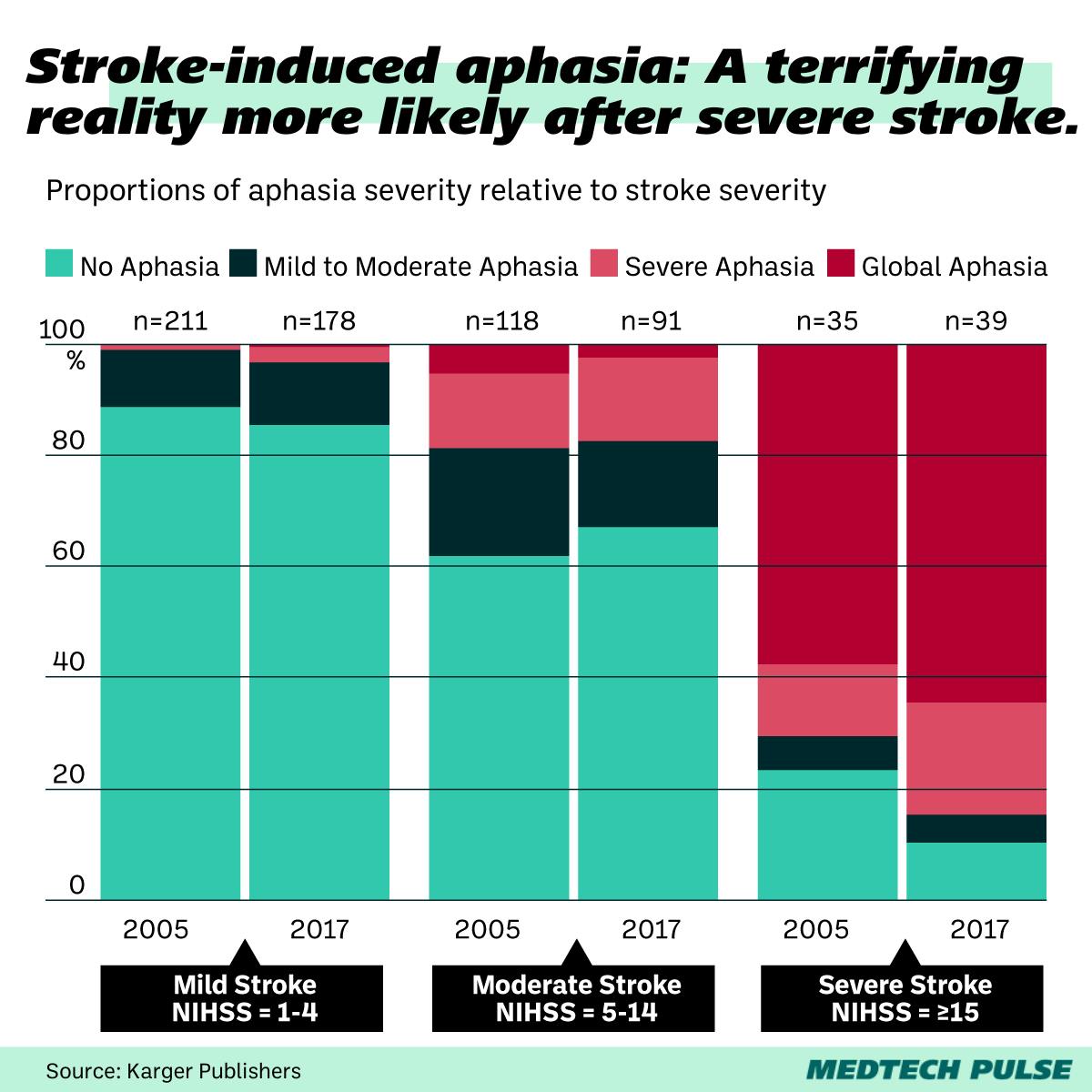

Aphasia, or the loss of ability to express or understand speech, can be a brutal consequence of stroke. LIS, though rarer than post-stroke aphasia, takes that nightmare to a new level for some stroke patients. LIS patients are aware but unable to move due to the complete paralysis of almost all their voluntary muscles—except for their eyes.

For Ann, years of physical therapy slowly gave her back her ability to cry and laugh, but speech still evaded her. She began to use a device to write using her eye and head movements, slowly typing letter by letter, maxing out at 14 words per minute.

Now, the UCSF team’s BCI is helping Ann express herself at nearly 80 words per minute.

Communication, of course, is not just about speech. Facial expressions are a huge part of human interaction. The BCI translates not just a voice for the text Ann transmits through the implant, but also approximated facial expressions.

All of that happens with the help of the system’s algorithms, which were trained for weeks on Ann’s brain signals and videos of Ann speaking pre-stroke, such as her wedding speech.

Ann’s daughter was one year old when she suffered her stroke. She knows “Mom’s voice” as the British-accented computerized voice of her communication device. Ann hopes this breakthrough can finally connect with her daughter through her more closely-approximated synthesized voice.

BCIs have been taking off

Ann’s BCI is a small rectangle of 253 electrodes implanted on the surface of her brain in an area known to be associated with speech. The electrodes were then connected to a physical cable that ran to a bank of computers.

But not all BCIs work in the same way.

If you’ve heard of BCIs before this story in any capacity, odds are you’ve heard of the brain implant chips built by Elon Musk’s controversial Neuralink or its main rival Synchron.

If you’ve been reading our newsletter for a while, you may remember when we discussed the brain-controlled electric wheelchairs BCIs have made possible.

Of course, getting these devices in patients’ hands (or, rather, heads) is a slower process due to the risk and personalization involved, especially for the more invasive devices. Yet, progress in this field has been incredible to watch, with more and more new mind-bending use cases cropping up in the literature—and headlines.

Here are some more medical BCI applications we’re keeping our eyes on:

- The robotic wearable IpsiHand became the first FDA-authorized BCI device in 2021, and it’s been helping stroke patients ever since.

- Blackrock Neurotech’s portable BCI allows patients to participate in research trials from the comfort of their homes. The company is also behind the high channel count next-gen BCI, Neuralace.

- While not strictly for medical applications, we’re also excited about Neurable’s BCI-enabled VR tech. Given what we’ve seen with VR applications in provider- and patient-facing environments, we’re interested to see how this technology might work in our industry, too.

Digital avatars as a medical tool

While the BCI involved in this case is doing much of the work, the real marvel is Ann’s digital avatar. It brings her to life in a way she recognizes and hasn’t been able to express herself for almost two decades.

While this is a particularly special use of a digital avatar, these representations are becoming a more useful tool in other areas of healthcare. Especially when it comes to telemedicine.

Exciting proposed use cases for digital avatars in the health world include:

- Haptic-enabled AR avatars that allow physicians to more intimately interact with patients in a telehealth setting

- “Digital twin” simulation of patient bodies for next-level precision medicine, such as those being developed by the European Commission-funded Virtual Human Project.

- Provider avatars to make AI-enabled digital health apps and services feel more personalized and human-like.