You can find out your biological age with a simple cheek swab. Welcome to the new frontier of DTC health.

Want to live longer? There’s a subscription for that.

Longevity startup Tally Health just launched its direct-to-consumer epigenetic home test kits. Tally claims their diagnostic kits can tell users what their “biological age” is—and how they can reduce it.

The test kits are based off founder David Sinclair’s Harvard lab research into epigenetics. This research resulted in a new model published in Cell last month that details how aging is related to the epigenome.

But Tally’s product isn’t just a test. It’s also subscription-based health guidance.

Tally subscribers don’t just receive at-home epigenetic test kits—based on a simple cheek swab. They receive customized diet and exercise advice (as well as recommendations to the company’s own branded supplements—some of which are included in the membership) to “lower” their epigenetic age.

The longevity market

Racing against the ticking clock of aging has become a popular venture in Silicon Valley.

Last year, Altos Labs made headlines for drawing billions of dollars in capital for their disease-reveral startup—including investments from the likes of Jeff Bezos and Yuri Milner. Other billionaire-backed longevity biotechs include Calico, Unity Biotechnology, and Elevian.

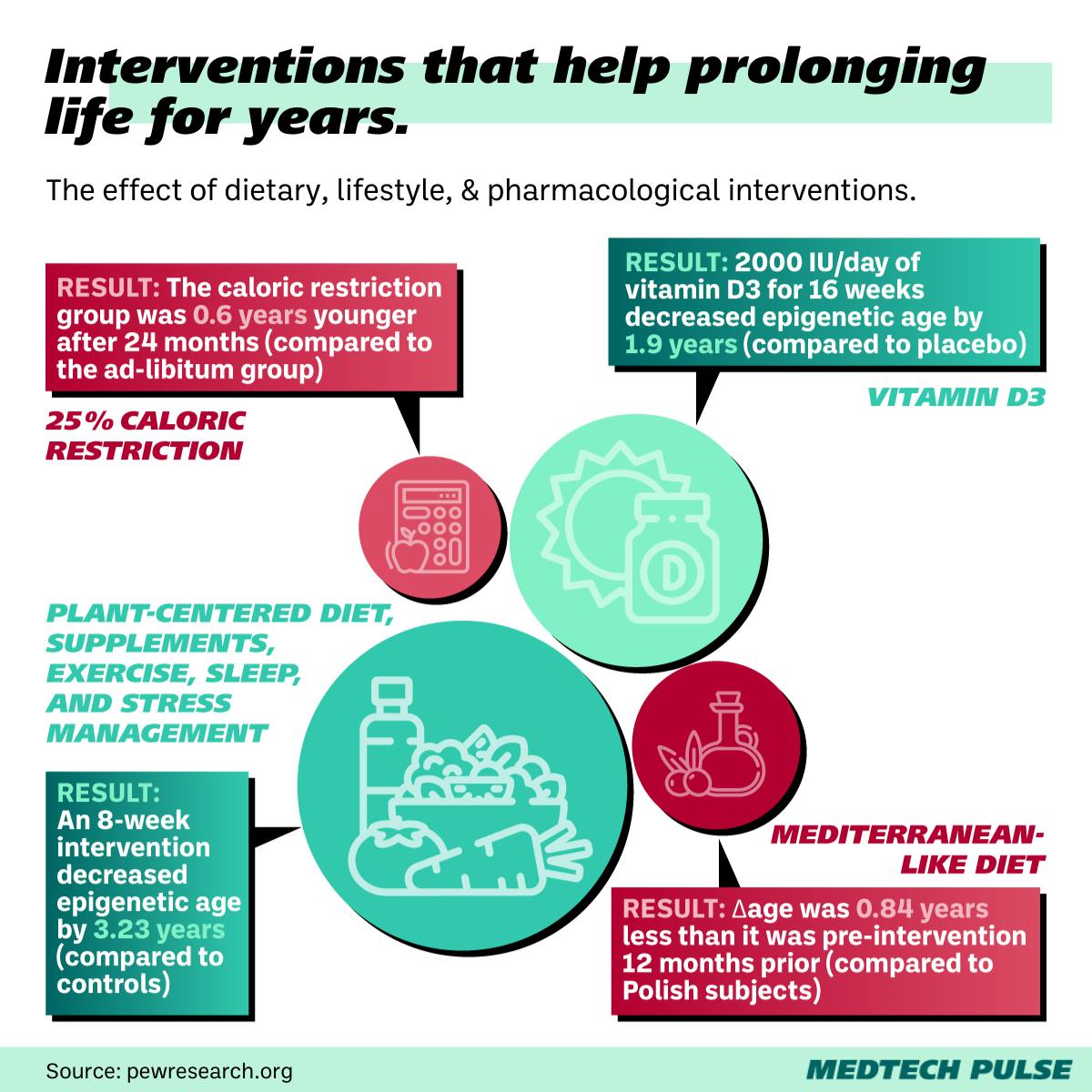

Beyond the flashiest funding deals, the ground-breaking research in this field is accelerating. Studies have uncovered connections between diet, drugs, and even sleep with epigenetic age reduction. The Sinclair lab research piggybacks off many of these achievements.

Nir Barzilai’s Targeting Aging with Metformin (TAME) Trial is a particularly buzzy example of this research. Barzilai—head of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine—has spent over a decade testing how certain drugs can extend the human lifespan.

However, regulation is tricky when it comes to this area. Aging isn’t—at least for now—defined as a disease. Thus, the U.S. FDA’s a “one disease, one drug” model of approval isn’t an ideal fit. Researchers’ approach—including Barzilai’s—is to use biomarkers as a proxy, using the clinical trials of the first statins as a model.

In 2015, Barzilai and a group of top-tier academic researchers met with the FDA to make their case for the TAME trial—and the agency agreed. However, funding became an issue.

In Barzilai’s words: “Those big billionaires, they want moonshots, they want a scientific achievement that will make people say ‘wow.’ TAME is not a moonshot. It’s not even about scientific achievement really, it’s more about political achievement.”

That’s why Tally’s subscription DTC business model is so exciting. Their approach is not just to give consumers actionable personal health data right away—which it does. They’re also able to collect this data over the long-term, contributing to the insights trials like Barzilai’s seek to move the technology forward.

A new frontier in preventive medicine?

As it stands, preventive medicine is concerned with avoiding tomorrow’s health concerns today. It uses monitoring of early disease markers and evidence-based health promotion practices to keep patients out of hospitals. Essentially, preventive medicine care relies on patients getting baseline care today to avoid more extensive care in the future.

Some of the best tools of preventive medicine are individual-driven—and not dependent on a traditional healthcare model or even provider involvement. Balanced nutrition, physical activity, quality sleep—all of these factors of a healthy lifestyle can be managed individually for most people.

That’s where scientific epigenetic data can be a fantastic preventive health tool—when provided with accessible evidence-based health guidance and a high level of data privacy.

Some critics are not convinced that epigenetic tests amount to a health tool—yet. To them, the current longevity offerings are biohacking dressed up in health marketing.

“These companies are layering on all this scientific language to give these tests a veneer of legitimacy, and the concern is that it could draw a lot of people in when there’s not good evidence to say there’s a clear health benefit on the other end,” said Timothy Caulfield, a health law and policy researcher interviewed by STAT about the Tally launch.

Caulfield’s criticism hinges on the fact that some studies have shown that genetic testing, as it currently exists, is unlikely to make meaningful changes in people’s diet and exercise behavior.

However, Tally executives point out that these previous studies haven’t been able to measure the impacts of behavioral changes on a cellular level.

“We aren’t offering the ‘quick fix’ but we do offer the much needed benchmarks which may finally provide the motivation and drive to course-correct,” said Tally CEO Melanie Goldey.

From our perspective, whether the test results have the capacity to change behavior depends entirely on the individual consumer’s intentions.

Paying over $100 for a home health test implies a commitment to improving one’s health. Previous studies involving tests conducted for other reasons—including routine health testing—would be unlikely to factor in that valuable intention.

Of course, there are valid concerns to keep in mind as we keep innovating in this field.

For one, there’s the concern that insurance companies may try to take advantage of this kind of information. Life insurance companies have already tried. As we strive forward in the longevity field, we must continue to prioritize data privacy.